LOVE LETTER TO LIMOGES:

It’s a reaction that I’ve never encountered more, however, than when I tell people—the denizens of Paris, Bordeaux, and Biarritz—where in France I live. When I say I live in Limoges, at first they fire me a pained expressionof squinty eyes as if they haven’t quite understood what I’ve said. But when it dawns on them that my place of residence actually is this little medievaltown in the Haute-Vienne, their chin jut quickly indicates that I’ve not made a good choice. As one delicate beehived blonde asked me through a swirl of cigarette smoke and a voice full of husk, ‘Are you lost?’

When asking locals why Limoges has such a bad rep, one declared definitively (and almost proudly) with a pump of their index finger that it is ‘The most boring place in all of France.’ They explained that it’s located smack bang in the middle of the “empty diagonal”—a region of France nicknamed the white space or France’s subconscious due to it being the most sparsely populated area in the country. The tones in which this white space was relayed to me conjured up some sort of land-bound Bermuda Triangle, as if the people who lived here were in danger of being swallowed up by the abyss of countryside that surrounded them, never to be seen again. And yet another local explained to me that comedians often interchange the word “banish” for being “limoger,” due to a famous general sending senior staff he considered useless here during World War I as it was as far away from the front as possible. To be limoger means to be put out to pasture.

But despite this, or maybe because of it, I have become a diehard Limougaudes. Sure, this isn’t Leonard’s Hydra, Beauvoir’s Paris, Smith’s NewYork, Bowles’ Tangier, or Baldwin’s Provence—a destination you pilgrimage to so as to nestle in their footprints or sip coffee in their cafés in the hope of imbibing the hallowed air where they became great—but there is an aura in Limoges that tells you, if you sit quietly enough and are willing to hear it, that great things happened here too. They just happened before greater things happened after them... usually somewhere else.

It’s an hour out of Limoges, for example, in the countryside of the Limousin, where a young Simone de Beauvoir spent her formative summer years holidaying at her grandparent’s vine-covered home. Relishing her freedom and savouring the solitude so hard to come by in Pairs, she got blissfully ‘drunk from reading,’ and it was here too, in 1929, during one of her last visits to the region, that Sartre visited her in secret, their clandestine meeting in the woods kickstarting their relationship at a time when Beauvoir’smother was still opening her letters.

Limoges was where a young Serge Gainsbourg escaped to, travelling here with his Jewish family under false papers in occupied France. The Resistance burgeoned around him due to the strong leftist leanings of the city’sinhabitants and because the surrounding forests offered refuge for guerrilla groups if hiding was necessary. It was here that a young conductor and violinist friend of the Gainsbourg family found a furnished hotel for them to stay in and even obtained for Serge’s two sisters the protection of the nuns at the school of the Sacred Heart, who, in something straight out ofTheSound of Music, gave the two high school students the key to the garden there, into which they could flee to in case of a roundup.

At 14, Gainsbourg attended a boarding school twenty-one kilometres from Limoges, in the village of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat, where even as a teenager he cut an elegant figure, drawing pencil sketches of the female form in his notebook and describing his more country-leaning classmates in letters to his parents as ‘hicks.’ At this boarding school, though, he was protected. His principal, upon learning of an upcoming raid by the militia, told Serge to go to the forest with an axe and tell any Germans he might come across that he was the son of a lumberjack.

It’s a region that has offered refuge to others in more ancient times too. As I go on my run each day over the Roman bridge that crosses the river Vienne and through the city’s botanical garden that houses over 1200 species ofmedicinal and aromatic plants, along with others used for food and dyes, I pass metallic gold scallop shells paved into the cobblestone pathways. These mark the trail for pilgrims on their way to the Spanish city of San-tiago de Compostela. Since the Middle Ages, these pilgrims would—and still do—rest their heads in the abbeys, albergues, and now Airbnbs of the region after a long day of travelling by foot.

It’s this kind of hospitable conviviality that is still alive in Limoges. It’s a place where neighbours invite you into their homes to eat saucisson and drink red wine, to view their antiques while you get allergies from their ancient cat, to tell you stories of the region because they’re proud of it too. Where antique store owners will give you the free rosary beads or spiky seashells you’ve been eyeing up, simply saying with a smile, ‘Cadeau.’ Or where the owners of your favourite Syrian Café will add handmade desserts of dates and pistachio to your Uber Eats order, with a handwritten notethanking you for yo

It’s where you can still find drinking holes that haven’t changed since the1950s, run by a buxom older woman who knows all the secrets of those who set down their glasses on her bar. Where people still say ‘Bonjour messieurset mesdams’ to everyone as they enter, and if you’re new to the bar, having stumbled upon it after a coldwave gig at the city’s one music hall, people will even come up to you, shake your hand, and introduce themselves be-cause it’s exactly like Cheers in an alternative universe. Even in one of the city’s trendier cafés, where ristretto and cold brews can be sipped, a patron will still say ‘Bon appetit!’ to you with a smile as you try to eat your salad gracefully despite wayward stems protruding from your mouth.

One of the city’s famed festivals is born out of this feeling of community. In 994, when rotten rye was consumed by large numbers of the population—with many growing nauseous and hallucinating as a result, and some even having their hands and feet turn black before falling off—those suffering from the “burning” epidemic congregated at the city’s churches. To implore God for his protection, a great gathering was organised around the relics of Saint Martial, the city’s first bishop and patron saint. These relics were raised and transported to a local hill as crowds followed, after which the epidemic is said to have ceased. To this day, a golden shrine containing the bones of this saint and a golden cup adorned with fish that contains his skull are paraded through the city’s streets, with crowds following and surging in thanks.

It’s a place where even the soil offers a sort of refuge too. Filled with kaolin that alchemises into the whitest porcelain teacups that fine folks sip from at Claridge’s, this mineral found in the dirt created the city’s economy and provided the livelihood of many of its inhabitants—and it still does today, as witnessed by the many porcelain shops that line the city centre. It’s also where the first union in France was created, on the cobblestone street parallel to the one where I live, to help the many workers who laboured in the porcelain factories earn their rights.

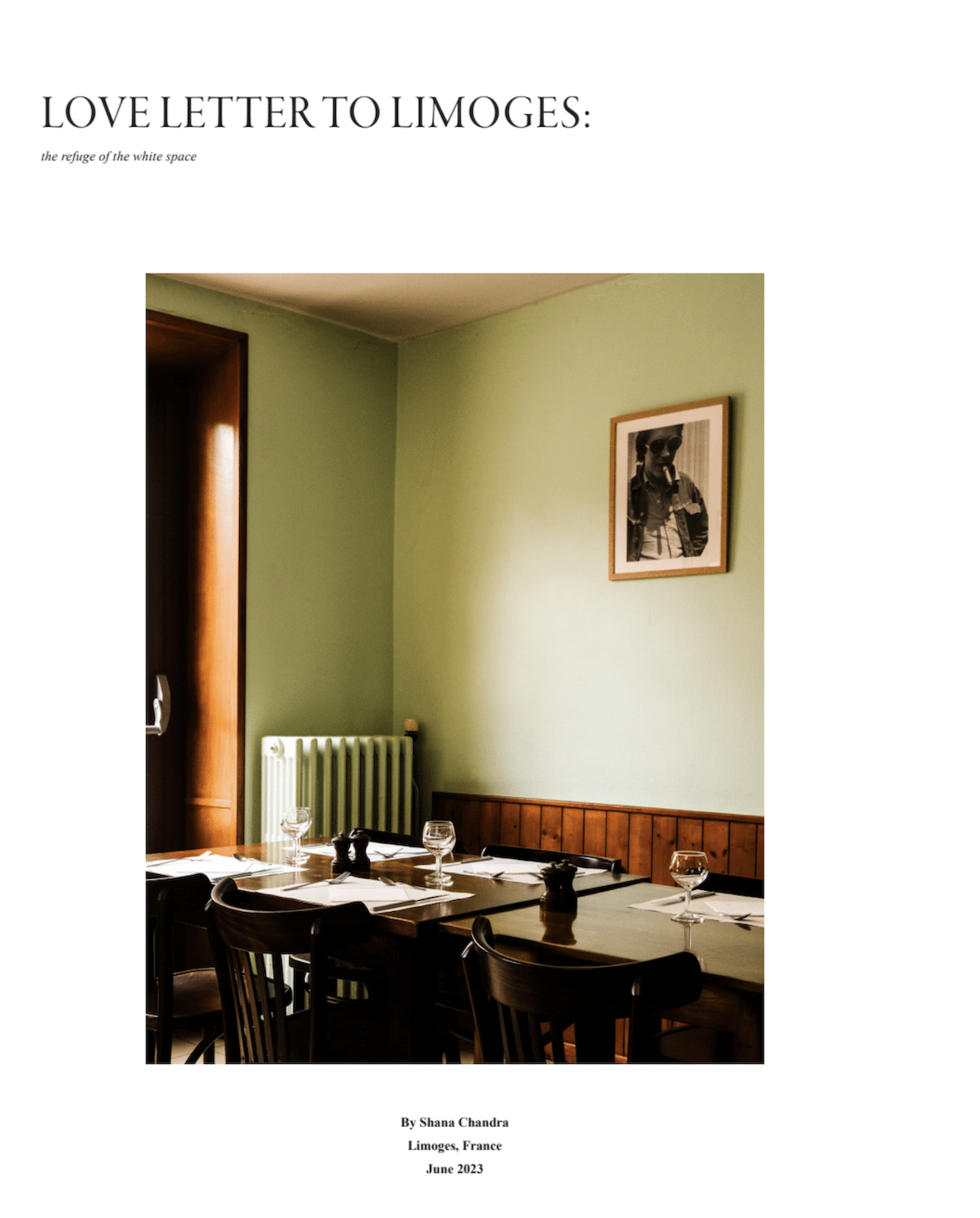

The city’s working-class roots hold strong here. It’s a place where huge displays of wealth are looked down upon, and when you pop down to a local canteen near the river—its mint green walls proudly displaying black-and-white photos of Serge, Jane, Catherine, Alain, and Romy—you’ll find local road workers resplendent in their fluoro orange vests, older retirees, and the well-heeled all sharing pitches of wine and cheese platters, and dining on local specialties cooked by a chef who dons a puffy white hat and who, before the lunch rush, shares a meal with the proprietor. And in the quartierde la Boucherie (the butcher’s quarters) in the old town, where the region’s famed rust-coloured cattle were once transformed into prime cuts of Limousin beef, the local chapel features a statue of Mary and Joseph holding Jesus as a baby. The child himself holds a kidney for nourishment—an odeto the neighbourhood’s working-class vocation.

It’s a rebellious attitude, too, that coats its inhabitants, which is perhaps why punk music thrives here. Housed in one of the historic buildings, with exposed beams in diagonal patterns that look like Roman numerals, is a favoured punk bar that has managed to survive the pandemic. Here, amongst paper plates of crisps and nuts put out for patrons to snack on, I watch the American garage punk band Paint Fumes unleash on the tiny dance floor, and when the grungy guitarist looks into the largely French-speaking crowd to ask how old the building they’re performing in is, the crowd, too busy swaying and swilling their beers, don’t answer him. But at that moment, it’s as if I can hear the ghosts of the building whisper back ‘old’ to him through the cracks of each of the hand-laid bricks that make up its ancient walls. And during the interval, when the whole bar goes outside to have a cigarette, a local high school teacher and radio DJ who also owns a second-hand record store in the city centre tells me that back in the 1970s and ’80s, when conscription to the army was still mandatory in France, some young men, refusing to join up, would break their own arms so they wouldn’t have to fight in wars they didn’t believe in.

It’s a city that sits upon many tunnels and cavities that were once used to store produce, as well as being the crypts of monks and saints. As if by sitting above these ancient routes, Limoges knows it is a transitory space, just as its famed river Vienne was once a route for Atlantic salmon and sea trout to travel along. One of the city’s more modern claims to fame is thefact that its train station was the backdrop of a Chanel N°5 ad. In it, the Parisian-pixie Audrey Tatou, with drops of the perfume at her wrists, only meets her lover when she leaves Limoges, the romance of their tryst blossoming elsewhere. It’s where national treasure and famed author Honoréde Balzac stayed for a while, drawing inspiration for his novel The Village Priest from the neighbourhood’s eccentric characters, porcelain factories, and bucolic surroundings, and it is in this region that the main character, Véronique, finds atonement through her devotion to fertilising the aridlands of the Limousin countryside.

This is the countryside about which someone—I can’t find who—once declared ‘that one life will not be enough to know all the greens of Limousin,’ and I wonder if Renoir ever drew inspiration for his greens from here,nbecause he was born in Limoges. There is a house that I walk past on theway to get my morning coffee that bears a plaque stating it as his birthplace before he became the famous artist of Montmartre. And down by the river, there’s a sign proclaiming that Molière once stayed at a house there, at 7 place Sainte-Félicité, when he was on tour with his theatre troupe in 1649. I wonder what sketches of Limoges and its people or which phrases may have come to him during his brief visit that he later embedded into one ofhis plays—a mannerism from a local, snatched and reproduced on stage.

It’s as if this is a place where seeds are dropped, and though you don’t often watch them bloom to fullness here, it’s a place where beginnings burgeon and start to transform into something else. It’s like the practice of the peasants in the hills of the surrounding areas who, to finish off their dregs ofsoup, pour wine in it to mop it up, the wine/soup mixture transforming into a new, in-between thing.

It’s an almost nascent atmosphere that speaks of magic, because you feel you are on the precipice that something is about to happen... even if it doesn’t. And maybe that’s the biggest reason why I love this place. When an American jazz singer stumbled upon the white space—albeit not near Limogesbut in a district called Lozère—she said, ‘It’s a place to which I reacted in a totally spiritual way, a place where nature bursts into you, where you can hear the rustling of the stars. I was pregnant when we got there, and I told myself: This is where I want my child to be born.’ It’s the rustling of the stars that I hear in Limoges and its surrounding countryside too, and it’s where I want my own stories to be born. And where they already have,