Michael Hutchence's Space Dog Days

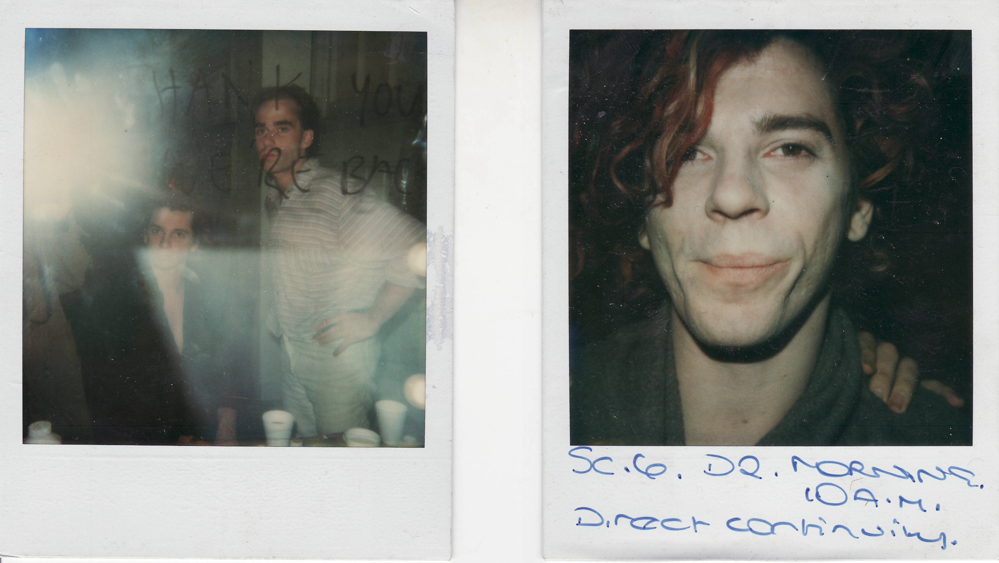

His first couple of films were re-purposed scripts from his mother’s interviews, but not long after, Lowenstein became immersed in the world of music videos, creating visual art for bands like The Ears, Hunters & Collectors and INXS at a time when music videos were more than mere advertisements. This lead to Dogs in Space, a film centring on a punk share house in 1980s Melbourne and starring a very young Michael Hutchence in the leading role. More recently Lowenstein created the documentary Mystify: Michael Hutchence, which showed a side of Hutchence that only those close to him knew. I sat down with Lowenstein to talk about the documentary, stealing film stock and exactly what the hell is wrong with the Australian film industry.

After your first film, Evictions, you got into the music video scene. Your first music video was for your housemate at the time; Sam Sejavka, the lead singer of The Ears. How did it come about?

We were living pretty much what’s portrayed in Dogs in Space. We were in film school, literally living in the house we ended up filming in the movie, with a whole bunch of other film students. And to help pay the rent, we’d pulled in this punk band. They arrived with all their hangers-on, and there was a lot of crossover between the band and film school. When it came time to for them to release a single, we stole film stock from the film school. We thought, ‘We’re in the perfect position to do a music video for this,’ and that’s kind of what happened. There was no money or anything, so we just did it, and that got played quite a bit. Not so much on television, but at band gigs. They used to play the music video at live venues before the bands were playing. It got played quite a bit, and the next music video we got offered was The Hunters and Collectors, ‘Talking to a Stranger’.

Michael Hutchence’s character in Dogs in Space was inspired by your housemate Sam, but I heard he wasn’t impressed with the character being based on him?

That story’s been going on since we made the film. But he was very impressed when he read the script. I remember him coming around to our house in East Malvern, reading the script and rolling around laughing. And I asked him if I could use his real name, not the surname of course, but could I use the name ‘Sam’, because I couldn’t think of a better name than Sam for this character. And so, to get his approval, I had to let him read it and he said, ‘Sure, use the name Sam.’ I think it was only after he saw the film he realised, or he changed his mind about being portrayed like that. I’ve bumped into him over the years, and I think in time he’s grown used to having his private life exposed on film for all to see.

Dogs in Space really brings up memories and feelings about living in share houses…

Right. A lot of my film is about family and the family you choose—your friends. Especially the friends you decide to live with or work with, like on a film crew that goes away for two or three months, and the collection you get from that. The sense of nostalgia—with me anyway because I’m a bit melodramatic—the sense of nostalgia comes almost a few hours after, when it finally says it’s over, then I start to go through the five stages of grief.

Why do you think Dogs in Space is considered a ‘cult classic’?

I can tell you a major reason why it stands out—it’s because the rest of the Australian film industry is so disappointing. After so many years of being involved with it, I would’ve hoped that there would be many films that are ‘seminal’ like Dogs, and yet there isn’t. There were a number of notable films in the seventies, which are still some of my favourites… But, I don’t know, it’s something that when we restored it ten years ago, we dug out the negatives and we put it up on the machines, scanned it in and everything so the colour was back and sharp, all the technicians are going, ‘Wow, this film hasn’t aged’. It’s not an anachronism of the times, it just hasn’t aged.

What would you like to see come out of the Australian film industry or what do you think needs changing?

I find Australians, and it’s something to do with their cultural cringe, they rule themselves out of—especially in the feature film world—the intelligent dramas that the rest of the world have created so well. A lot of Australian cinema is very parochial, and we embrace what I call the ‘Cinema of the Idiot’. We love these characters that are actually idiots, like Crocodile Dundee, like The Castle. I’m not criticising these films in any way, but we don’t embrace intelligent characters, there’s no Sherlock Holmes coming out of Australia. There’s no, ‘let’s do a really intelligent detective story’, you know? But we don’t; we resort to the outback, we resort to country towns, we resort to congenial characters, but really, they’re fucking morons. In my own experience, [those with] the power to say, ‘Yes you can go forward on this’, say, ‘Shouldn’t we just let the British do that? They do it so well.’ I’ve literally had that come out of assessor’s mouths. And you just go, ‘Ok, so you want a film about an endearing moron.’

Having collaborated with Michael for so many years, what was an interaction you had with him that left an impression with you, that personified him for you?

There is that story that was early on in our friendship, when we shot ‘Burn for You’ up North and then I met up with him not long after at the Cannes Film Festival, that kind of encapsulated something of why I liked him. We stayed up all night, partying at the different bars and parties at the film festival after they played. It was sort of before mobile phones and everything, and we’d gone to a breakfast meeting I had, that I was supposed to pitch a film at. Michael came along, and we were there with our $10 orange juices, which back then were like $100 orange juices, and I’m pitching this film and it’s not going so well. I think we’d been discussing the idea that might have been the genesis of Dogs in Space a little earlier that night, and I suddenly just segued into it, because this thriller thing I was talking about wasn’t going anywhere and the producer was looking very blankly at me. I was like, ‘There’s that one, but there’s also like this other one, it’s about a bunch of hippies and punks living in a house in Melbourne.’

At this stage Michael had fallen asleep at the table, he’s just passed out, and I said, ‘It’s got Michael here in it’ and he looked up and said, ‘Am I?’ And then he went back to sleep again, and the producer goes, ‘Wow, that one would really interest me,’ but we never saw that producer again. Afterwards, the band were meant to come and pick Michael up, and they were running late. And I remember sitting in the sun on the steps of the Australian Film Commission office and Michael was lying there, falling asleep again, and David Stratton walks by and drops a ten-franc coin into his hands. Michael had just heard his song was number one in France, and he looked up and holds up the coin to David Stratton and says, ‘Thanks mate, I needed that.’

With Mystify, was there a need to dispel a certain image about Michael’s persona or kind of highlight something about his life or about his death?

Well, it wasn’t so much dispelling anything, it was just I just wanted an authentic portrait of him that a lot of us that were involved in the film actually knew. None of us could recognise the stories that were being left behind, whether it was from a mini-series, or tacky documentaries or things on YouTube, you just go, ‘Hmmm, that’s not really the person I knew…’ I remember very clearly watching a stand-up comedian on television, and he used the rumour about autoeroticism and Michael as a punchline. And I do remember that being the spur of the film.

I actually knew the real details which you see exposed in the film, about the autopsy. And being closely involved with the people, I knew how the rumour of autoeroticism appeared. I was at the funeral home for the first six-seven weeks of his death and no one even mentioned that. Then I think Paula (Yates, Hutchence’s partner) did a 60 Minutes interview and there it was, and suddenly the world goes crazy, that’s all they remember. And when I heard the comedian make that joke, I thought, ‘Right it’s time to do something about this.’ And all I had to do was tell the truth.