No Wave Strumming The Now:

Essay by Shana Chandra as featured in Jane Magazine, Issue 9.

Its point was to use its instruments to make transcendental turbulence and blasting imagery for its musicians and makers to swoon, rage, and screech to, and if the audience came or dug, it didn’t matter. As one of its spunky figureheads and spoken word poets, Lydia Lunch, said of the scene, likening it to dada’s rejection of logic, reason, and capitalist aesthetic, ‘I wasn’t expecting the toilets at CBGB’s to be the bookends to Duchamp’s urinal, but then again, maybe 1977 had more in common with 1917 than anyone at the time could have imagined.’ And from this corrupt, bankrupt, seething New York, out of which music and super 8 film retched—a city that President Ford refused to bail out and that, at the time, felt as wretched as the world does at this moment—maybe 1977 has more in common with 2020 than anyone in our time can imagine. And just maybe, No Wave can teach us something.

Nihilistic? The whole fucking country was nihilistic. What did we come out of? The lie of the Summer of Love into Charles Manson and the Vietnam War. Where is the positivity? I’m supposed to be fucking positive? Fuck you! You want positive, go elsewhere. Go find a different lie.

—Lydia Lunch

We came out of destruction.

—Thurston Moore

Through this period of disruptive, transgressive, DIY expression came the kind of creativity you have to eject because it burns within you so bad, one rendered from the wasteland of a bankrupt New York, where dilapidated buildings were up for the squatting, baring their toothless grin of smashed in windows, where trash bathed the streets, the serial killer summer of Sam gave nightcrawling a new meaning, and a hustle to pay rent was easy to come by. Those who had the money and a less feral disposition left, chased out by swarming rats churning up Avenue B. Those who saw the promise in abandoned warehouse spaces and the glam, drag, and dress-who-you-be spirit of the New York Dolls, or felt the poetic spit of Patti Smith slap their faces, jumped on Greyhound buses to start something new.

Translating the sordidness, the squalor, and the sex to discordant rhythms and transgressive images, the No Wave harbingers made do with what they had, turning the city’s blank canvas into their art and turning their Lower East Side hangouts like CBGB, Max’s Kansas City, and the Mudd Club into their wild living rooms each night, where they most importantly turned towards each other. Filmmakers shot their friends with grey market cameras to the rubble of buildings torched by landlords for insurance payouts when they learnt that there was money in destruction. Looters lavished as power cuts plagued, but then you hooked up your power from your next-door neighbour’s line anyway, and you showed your short films at those same friends’ gigs. Music was never the point, but using your instruments to strum your pain was. No one’s creativity was dumped into a one-skill- only box because you couldn’t afford to have one skill only.

Flash forward to our apocalyptic present: fires raging as the Earth weeps red hot flames as her revenge, the absurdist performance art of politics where melting hair dye and stagnant flies become symbols of the deeply awry, a serial killer of a virus cursing the streets silent, and protests still screeching for basic human rights that should never have been taken. This is the wasteland of our now, one that has residues of the past, as in its breakdown we see the fractures of capitalism barely holding our pandemic-ravaged society together.

But transmuting something from nothing, transmuting beauty from psychic pain or rage, or from somewhere where no one else sees it, has always been the skill of the artist, and right now, when more and more of our local clubs, gig venues, and art galleries are shutting their doors, as confinement turns our physical landscapes more desolate and our minds more manic, the very place where creatives commune and congregate, the place where DIY expression comes through is the technological: the rolling squares on our phone where artists can express and reach their audiences, the podcasts that can express dissenting viewpoints, and the web of network that transcends time zones and coordinates to connect individuals, disparate but synchronous in their howl. Right now, these are our wild living rooms where we can congregate, so we need to use them wisely, turning the angst into bloom, creating culture instead of too quickly cancelling it, and learning from our predecessors, who at a time as apocalyptic as ours had an anarchic vision that changed the landscape of our art forever. As Alan Vega, the “godfather” of No Wave and the wise sage of the band Suicide once said, ‘Everything is inherently good and inherently evil; it’s just how you use it.’

We’d take over buildings to have art shows. We dumped a car in the East River as a part of a film, and published photographs of it in The Soho Weekly News, and nobody ever said anything. You can’t imagine the freedom that we had. The middle class had abandoned the place, and we just walked in and took it.

—Scott B

Not knowing what you are doing is sometimes better. If you know what you are doing you probably won’t do it, because you’ll think, ‘I can’t do it that way.’ If you don’t know, then who says you can’t?

—Amos Poe

What the pioneers of No Wave did was voice their utter rejection of society by crushing the structures of music, film, and performance art that had defined it before them. Part of it was due to the DIY ethos of a bombed-out and bankrupt New York, because all you had was what was in front of you. So, actors sang, artists acted, and everyone was part of a band because you needed band members and it didn’t matter if they could play. Not knowing how to do something wasn’t a problem; it was better if you didn’t. In the documentary Blank City, John Lurie remembers how he didn’t let anyone know he could play the saxophone and chose to appear in movies instead: ‘Nobody was doing what they knew how to do. If you knew how to do something, it was kind of like “No no no no, you can’t have any technique.” Technique was so hated.’

This philosophy of being inventive with whatever you could find applied when rallying equipment too; to get money for his second film, Lurie staged a burglary of his saxophones and used the insurance money to fund it. Nancy Arlen, when first rehearsing for the band Mars, used paper bags instead of a drum kit. And then when you did find equipment, you played it new.

Lunch and her band, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, didn’t play their instruments; they used those instruments to fracture the musical modes of melody and tone to screech their pain in fierce ten-minute sets. Amos Poe made a full-length movie, The Foreigner, on one of those mythically stolen Super 8s, out on the crumbling streets, unleashing his friends Debbie Harry, Eric Mitchell, Anya Phillips, and Patti Astor onto the screen. He edited his movie, Blank Generation, in one night, on speed, because he only had enough money to rent an editing suite from the Maysles brothers for 24 hours. Alan Vega, inspired by a drum machine, spent his last $30 buying one from a couple out in Long Island, who told him it belonged to their young daughter who used it for her poetry but who had committed suicide the year before, and he named his band Suicide after that. By not being restrained by money to make it “right,” these artists broke away from the rules of before, saying no by creating a better alternative, just with what they had. It was rambling and raw, but so were the lives they had run away from and their current ones too.

And in this world now, where many of us are sick of slamming ‘No!’ every day to misogynist political leaders, to the corrupt one percent, to cowboy policemen kneeling on necks, to government censorship of our bodies and our voices, saying no by creating something new, using our art as protest even if we don’t get anything back, is the most powerful thing we can do. Think in the vein of K-Pop stans who hijacked and drowned out the #whitelivesmatter hashtag that had morphed towards racist backlash by clogging it with videos and images of their musical idols, in a spirit that was completely No Wave. As Lunch asks, inviting us to do as she did, ‘Why don’t you create something I’ve never heard before?’

Different disciplines came together. There were filmmakers, artists, musicians, poets. We would be making a racket in a studio one day, and shooting a movie the next day.

—James Nares

It was so eclectic, it was so diverse, it was so many different kinds of people coming together that needed to just get it out. No forethought, no afterthought, no ambition, no thoughts of the future.

—Lydia Lunch

The individuals who atomised together, coalescing under the tag of what we now call No Wave, were what filmmaker Nick Zedd describes when he first stepped into their nightly gig spot CBGB: ‘people like myself—outsiders, freaks, misfits.’ To be an outsider, freak, or misfit means you have to retain an outsider status even if and when you find others like yourself. That’s where Lunch’s eclecticism and diversity of ‘different kinds of people com- ing together’ comes in. These individuals grouping together in bands and film collectives were different to each other. Their projects were different, but their binding mission was to ‘get it out,’ in whatever artistic vomit they could project, with whomever they could find because, ultimately, art is an expression for the person who needs to expunge it before it consumes them.

In this way too, No Wave had no care for any audience to cater to, because having an audience wasn’t the point, and because having an audience in mind locks you into turning the capitalist cog. But if an audience did happen to find your artistic vomit, well, that was just a bonus. As filmmaker Beth B said, ‘It wasn’t about success, it wasn’t about being commercial. Success today is about how many likes I’m gonna get, it’s all about “Have you received back?” And that wasn’t our spirit because there was such a need to get it out.’ ‘Make it because it burns inside of you,’ says Lunch, and because you have the chords, vocal or instrumental, to exorcise it so that others who don’t have the burn or the means to do so will glow within it.

A way in which this collective individualism spewed out musically was that within the writhing four years of 1976 to 1980 in which No Wave was a thing, the four bands that epitomised the era—Mars, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, Contortions, and DNA—went through three or four versions of the same band, often with the same people. They left bands and formed bands and reformed bands with no love lost between the comings and the goings, because the point wasn’t the band as a whole but the individual expressions of each member in the band. When James Chance left Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, Lydia Lunch knew the non-participatory ethos of the band was not something Chance could sustain: ‘But it wasn’t long after James was in the band that I think we both knew. First of all, I wanted no interaction with the audience. It had to be a cold vibe to keep it separate ... I saw that James couldn’t control himself and had to be down there mingling and fighting and biting the crowd when need be.’ But Lunch still let Chance’s new band, Contortions, practise in her Delancey St studio/loft space.

In the end, it is collectives of individuals that gain traction the quickest. Groups of people chorus together using the power of their combined voices to move things forward. But with our technologies now that allow like-minded people to group together across boundaries that are no longer there, it is important not to clot the flow with the necessity for us to be exactly the same or to have the same opinion. Because as individuals who remain within a group, we are not just the great gaping masses of audiences they want us to be, however much we are scrutinised, monetised, and herded to be. We do not have to think the same and to be deadened to our own bubbling opinions. Remaining an individual is a rebellion to the powers that be who wish to group us into an algorithm, now more than ever before.

Pleasure is the ultimate rebellion. It is the only thing. We have to take back pleasure. Because this campaign of terror and fear and homicidal genocide the world over kills our capacity for pleasure by numbing us.

—Lydia Lunch

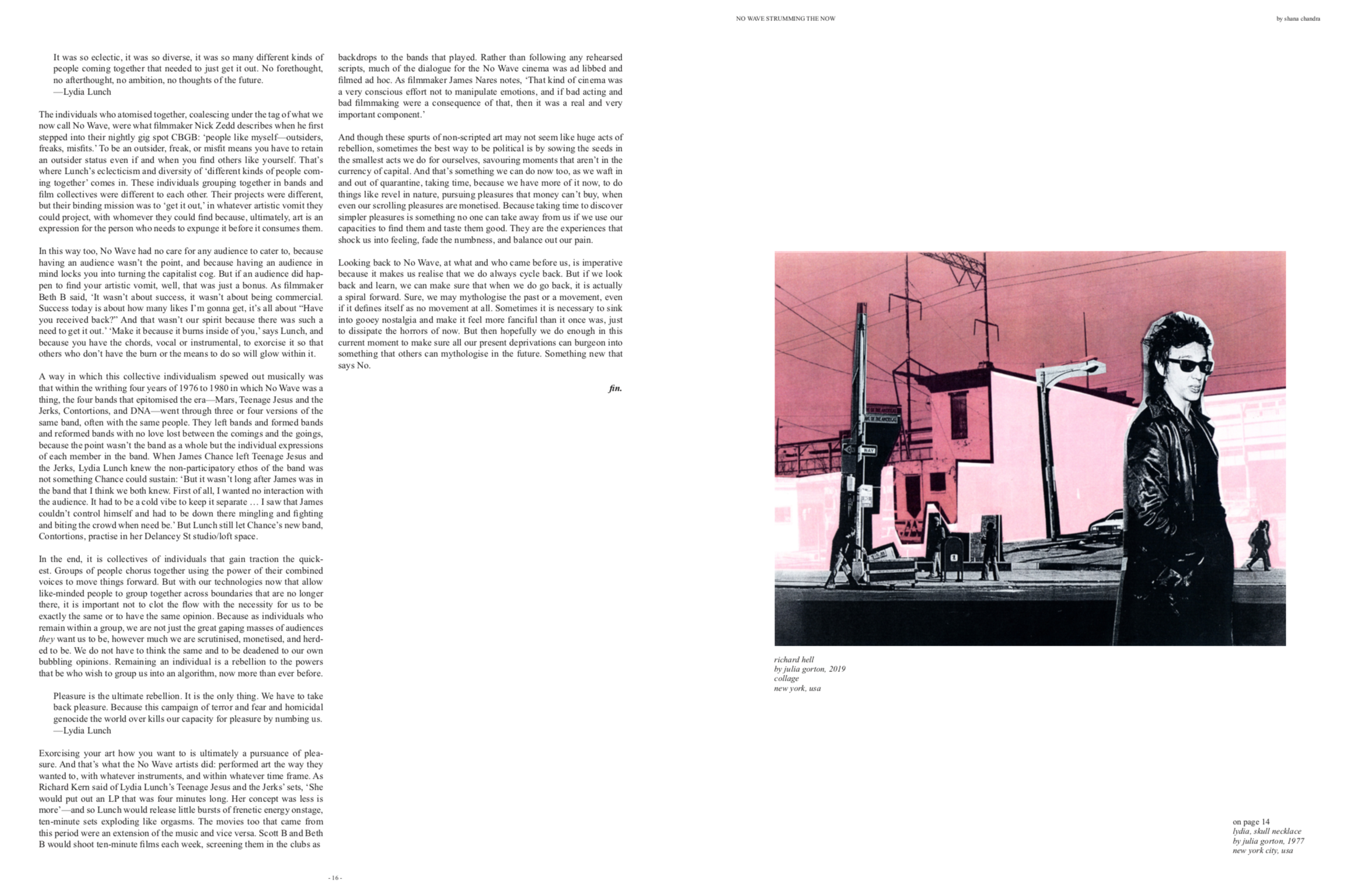

Exorcising your art how you want to is ultimately a pursuance of pleasure. And that’s what the No Wave artists did: performed art the way they wanted to, with whatever instruments, and within whatever time frame. As Richard Kern said of Lydia Lunch’s Teenage Jesus and the Jerks’ sets, ‘She would put out an LP that was four minutes long. Her concept was less is more’—and so Lunch would release little bursts of frenetic energy onstage, ten-minute sets exploding like orgasms. The movies too that came from this period were an extension of the music and vice versa. Scott B and Beth B would shoot ten-minute films each week, screening them in the clubs as backdrops to the bands that played. Rather than following any rehearsed scripts, much of the dialogue for the No Wave cinema was ad libbed and filmed ad hoc. As filmmaker James Nares notes, ‘That kind of cinema was a very conscious effort not to manipulate emotions, and if bad acting and bad filmmaking were a consequence of that, then it was a real and very important component.’

And though these spurts of non-scripted art may not seem like huge acts of rebellion, sometimes the best way to be political is by sowing the seeds in the smallest acts we do for ourselves, savouring moments that aren’t in the currency of capital. And that’s something we can do now too, as we waft in and out of quarantine, taking time, because we have more of it now, to do things like revel in nature, pursuing pleasures that money can’t buy, when even our scrolling pleasures are monetised. Because taking time to discover simpler pleasures is something no one can take away from us if we use our capacities to find them and taste them good. They are the experiences that shock us into feeling, fade the numbness, and balance out our pain.

Looking back to No Wave, at what and who came before us, is imperative because it makes us realise that we do always cycle back. But if we look back and learn, we can make sure that when we do go back, it is actually a spiral forward. Sure, we may mythologise the past or a movement, even if it defines itself as no movement at all. Sometimes it is necessary to sink into gooey nostalgia and make it feel more fanciful than it once was, just to dissipate the horrors of now. But then hopefully we do enough in this current moment to make sure all our present deprivations can burgeon into something that others can mythologise in the future. Something new that says No.