Space is the Place:

I know which one in the photo is my dad because I can still see that cheeky smile propping up his horn-rimmed glasses, and because, just like me, hewas always the shortest in his class, and so, in school photos, he had to stand in the top left-hand corner, just like I did. But the reason why I need to locate him by looks rather than by name is because during his time at Marist Brothers, my father was forced to change his Indian name, Satish, the one I knew him through, to that of a saint—as if the brothers in black habits who called him Francis would only recognise him on their terms, in the language of their religion, choosing to erase in white the simplest form of Indian identity with which he was born: his name.

My father was given a Sanskrit name that he used for most of his life. But as Malcom X pointed out, African American slaves and their descendants were forbidden even to use names that bound them to who they were, to their lives and culture in their motherland of Africa before they were stolen. It was their “masters” who gave them their names once they were “bought.” Malcolm X therefore spat out and vehemently rejected the slave name Little that he inherited, that was forced upon his ancestors when they slaved on plantations—a particularly apt name for a power-hungry coloniser to give to his subjugates. Instead Malcolm chose X to replace it. This was the X of the unknown, the X that the illiterate used to sign their names with wherever English was the language of power, the X that has now become synonymous with his name and has gone down the annals of history.

‘I have many names. Names of mystery. Names of splendour. Names of shame. I have many names. Some call me Mr Ra, others call me Mr Re. You can call me Mr Mystery.

But it was another African American man, Herman Blount, who decided to go one step further. He not only rejected both of his names, and with them their colonising Christian origins, but also the very place where he was given those names: Alabama in the deeply segregated South in the 1910s. It was these names and this place that already trapped him in a “history” narrated in the grammar of slavery, racism, and colonisers, from the very moment he took his first breath. So, as his notoriety as a musician grew, he eschewed the inequities that were inherent to an Earthbound persona and adopted a new one, choosing the name for this being to be Sun Ra, a perfect blending of Egyptological and cosmological elements that he juiced to form his own Afrofuturist radical spiritual philosophy, aesthetic movement, and musical genre that he not only lived by but also embodied.

He chose the place he came from to be Saturn rather than any X on Earth, visiting Earth only to save African American people from their bondage to it. In so doing, he created beautiful narratives subversively free of the systematic slavery and colonialism that would have dictated his past and present if he had not chosen those alternative frameworks. He showed people that they didn’t have to buy into the narrative that was forced upon them, but that they could create a narrative that was thought-provoking, tongue-in-cheek, avant-garde, serious, and, most important of all, fun—all at the same time.

‘In my music, I speak of unknown things, impossible things, ancient things, potential things. No two songs tell the same story. They say that history repeats itself, but history is only his story. You haven’t heard my story yet. My story is different from his story. My story is not part of history. Because, history repeats itself, but my story is endless.’

In re-writing his narrative, Sun Ra looked to ancient Egypt, a time when African power was at its glory. A time when colossal monuments such as the pyramids were created, and which to this day are pervaded with mystery; we still do not understand the mechanics of how they were formed, by the hands of an ancient civilisation. It was a time when no white power structure brushed this civilisation with erasure. Hence the Ra of his name, which came from the Egyptian god of the sun, endowed Sun Ra with a mythic status, not a human one, and this, for Sun Ra’s ideology, was important. Being Earthbound, being human-bound, meant being race-bound, and therefore shackled to history. By choosing myth, Sun Ra chose an eternal narrative that lies outside the parameters of history. And by choosing mystery, or “my story,” he was adopting an ideology that was the antithesis of the knowledge that is based, taught, and evaluated in an education system whose foundations are steeped in the West.

‘All planet Earth produces is the dead bodies of humanity. That’s its only creation. Everything else comes from outer space, from unknown regions. Humanity’s life depends upon the unknown. Knowledge is laughable when attributed to a human being.’

But Sun Ra’s Sun also hints at his predilection to outer space, a place where the colours and confines of this world and its hierarchies are unknown. Sun Ra had to look to outer space to release himself from these confines, because on Earth, not being white meant he always was and will be the “other.” But by touting himself as an angel from Saturn, part of an ‘angel racefrom outer space,’ he hints it is we humans and our Earth, with its inherently racist ideologies, that become the devilish other.

‘They don’t look like they’re having fun. I want people to laugh at thecostumes I have on. Why do astronauts wear what they wear? Why do soldiers? Because it makes people notice them more. The musicians have a perfect right to join the crowd and say, “We’re going to wear this; this is how I feel.’

Nowhere did Sun Ra exhibit his metamorphosis more than in his dress and the music that he conducted and jammed with his Arkestra, embodying his new name and his new story to its fullest potential so that its aura pervaded him and his band. Although many would call what he wore his costumes, no one ever saw him in anything else; they were his dress, whether he was on stage or going to pick something up from the corner store. His sense of dress was a homespun splendour, riffing on the ancient Egyptian symbols of the past with an outer-space future: a mish-mash of costumes rescued from a production of Madame Butterfly by the Chicago Opera, remnants salvaged from the Garment District, and gifts of homage from fans—as improvised as impromptu drama games where you grab an item from a closet and run with the character it tells you. The most famous image of Sun Ra, taken from the opening images of his Afrofuturist origin film Space is the Place, has him in a Tutankhamen-style headdress affixed with a golden orb between two antennae, his vermillion and bronze cape flapping and embroidered with gold tridents with fire at their heads. His costumes helped to reinforce the syncopated, spontaneous jazz he played, in a form of synaesthesia: ‘Costumes are music. Colors throw out musical sounds.’

‘You can’t say, “One teaspoon of this, or one teaspoon of that.” Like a musician, you improvise. It’s like being on a spirit plane; you put the proper things in without knowing why. It comes out wonderful when it’s done like that. If you plan it, it doesn’t work.’

Sun Ra’s ‘colors of musical sounds’ with the Arkestra ensemble would last for 12-hour practice sessions, with sermons from Sun Ra in between, where he’d spout his knowledge on Egyptology and space, an extension of his narrative and dress sense, until they all became inextricable. The genre-defying music, which abandoned written melodies and formulaic narratives for intuiting the mood of the ensemble and the audience as they played in free improvisation, was described by music critic Jez Nelson as ‘big-band swing,’ ‘space-age funk,’ and ‘proto-rap’ all at once. Sun Ra’s space-age sensibilities meant that he also incorporated cutting-edge technologies into his music via the instruments he played, introducing audiences to electronic keyboards for the first time. There was the Solovox, which ‘emulated the sustained sounds of strings,’ but it is the Moog synthesizer he is most known for, adapting its Model B version for his own needs and becoming the first artist to record using it.

‘I’m not real. I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you were, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. If you were, you’d have some status among the nations of the world. I come to you as a myth … I come to you from a dream the black man dreamed long ago. I’m actually a present sent to you by your ancestors.’

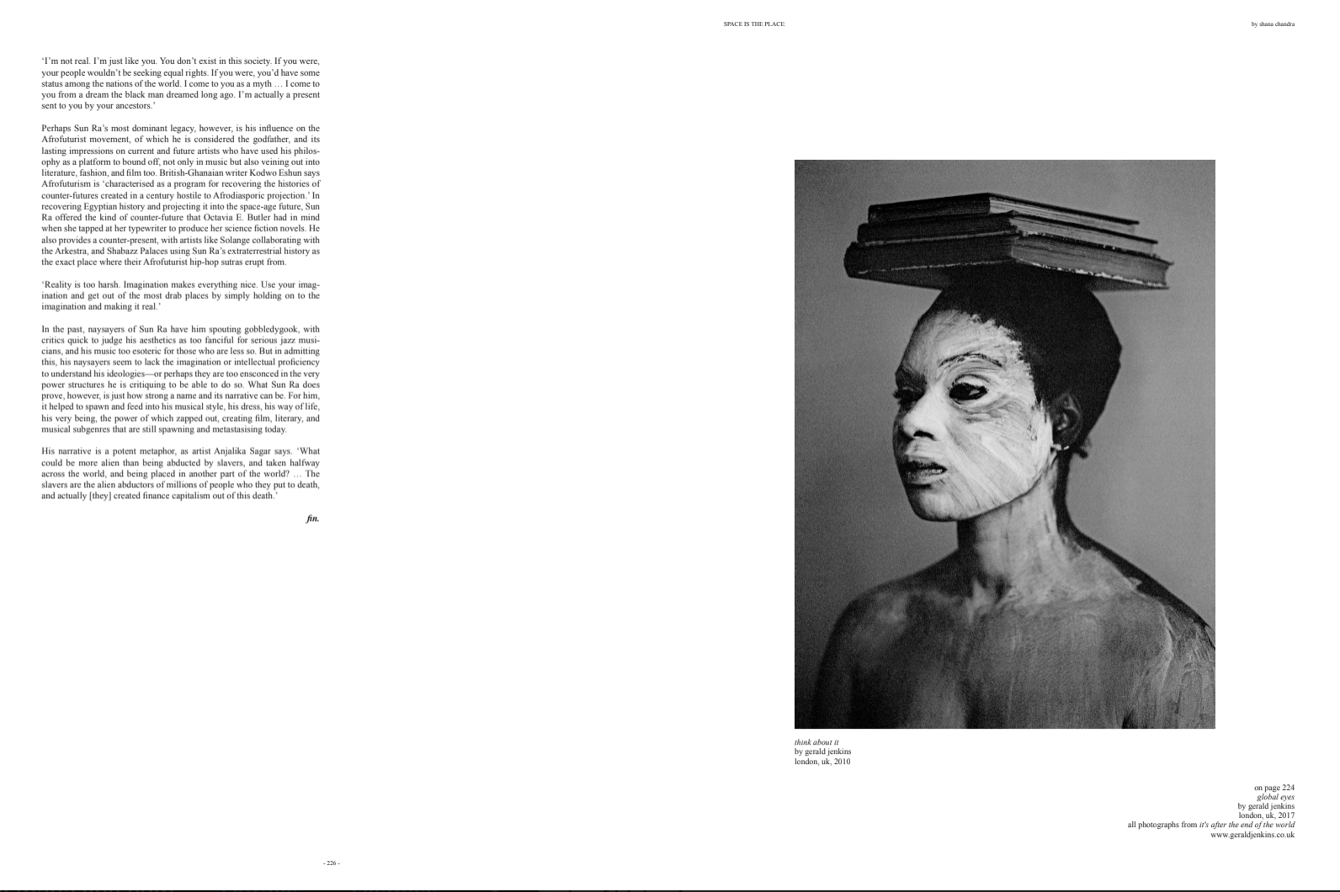

Perhaps Sun Ra’s most dominant legacy, however, is his influence on the Afrofuturist movement, of which he is considered the godfather, and its lasting impressions on current and future artists who have used his philosophy as a platform to bound off, not only in music but also veining out into literature, fashion, and film too. British-Ghanaian writer Kodwo Eshun says Afrofuturism is ‘characterised as a program for recovering the histories of counter-futures created in a century hostile to Afrodiasporic projection.’ In recovering Egyptian history and projecting it into the space-age future, Sun Ra offered the kind of counter-future that Octavia E. Butler had in mind when she tapped at her typewriter to produce her science fiction novels. He also provides a counter-present, with artists like Solange collaborating with the Arkestra, and Shabazz Palaces using Sun Ra’s extraterrestrial history as the exact place where their Afrofuturist hip-hop sutras erupt from.

‘Reality is too harsh. Imagination makes everything nice. Use your imagination and get out of the most drab places by simply holding on to the imagination and making it real.’

In the past, naysayers of Sun Ra have him spouting gobbledygook, with critics quick to judge his aesthetics as too fanciful for serious jazz musicians, and his music too esoteric for those who are less so. But in admitting this, his naysayers seem to lack the imagination or intellectual proficiency to understand his ideologies—or perhaps they are too ensconced in the very power structures he is critiquing to be able to do so. What Sun Ra does prove, however, is just how strong a name and its narrative can be. For him, it helped to spawn and feed into his musical style, his dress, his way of life, his very being, the power of which zapped out, creating film, literary, and musical subgenres that are still spawning and metastasising today. His narrative is a potent metaphor, as artist Anjalika Sagar says. ‘What could be more alien than being abducted by slavers, and taken halfwayacross the world, and being placed in another part of the world? … The slavers are the alien abductors of millions of people who they put to death, and actually [they] created finance capitalism out of this death.’