Wilding our Hearts:

There’s a moment in our interview when Gehman says, ‘I used to get overwhelmed because I used to think there’s so many places I want to go, and so many things I want to do, and so many things I want to read about or try out, but when am I going to be able to do this, and how is it ever going to happen?’ It is then that I get a flashback of her as a young child, where I imagine her looking into a crystal ball and seeing images of her life. When the ball has finished replaying her life scenes—heralding the LA punk scene of the 1970s, starting her fanzine Lobotomy, putting on shows at cult clubs The Roxy and Whisky a Go Go, hanging with Iggy or Kurt as a music journalist, writing her seven books, touring with her bands The Screaming Sirens, The Ringling Sisters, and Honk If Yer Horny, travelling the world as a belly dancer, or reading tarot and banishing ghosts from peo-ple’s homes—there’s a moment when she looks up from the ball and, with a bewitching nose twitch and an eye twinkle, says to the crystal ball, ‘Yeah, I know that, but what else?’

It’s a life lived by someone who wears self-assuredness like a leopard-print coat but also has the prescience to listen to the mystical signs that point her ruby slippers onto the right yellow brick road to dance upon. It’s a combination that paves her life with a glittering freedom that others envy because their own ruby slippers are clouded with inhibiting doubt. Gehman feels the doubt too but forces forward until it is left in her wake. As Nina Simone once said—and it is a motto that Gehman embodies—‘I’ll tell you what freedom is to me. No fear. I mean really, no fear.’

You were born in upstate New York but moved to Los Angeles as a teenager, where you were part of the burgeoning punk scene that coalesced in the mid to late ’70s. What was Los Angeles like back then?

This was in 1975, so I was fifteen, and I turned sixteen a few days after. My family had already been [in Los Angeles] for acouple of months, and I finished out a semester at boarding school. Before I even left, I saw that Queen was playing, so I got tickets by writing away for them. I took the bus down to the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium wearing a1940s evening gown with a 1920s purse and hiking boots on. I looked like someone that would’ve been from the late 1990s or early 2000s, but nobody then really looked like that. I had henna orange hair down to my waist and sequins all through it.

I went there alone, and I sat down in my row. As soon as I sat down, this guy with silver hair—that I immediately saw and thought Wow, that is a hot old man—turned over to me and said ‘Would you like some of this?’ and he handed me a joint. I took a puff of it and I said ‘Thank you,’ and I looked at him to hand it back and I realised it was Tony Curtis. We were talking, because the concert hadn’t started yet, and I saw these two boys walking down the aisle. One didn’t have a shirt on and was wearing black satin pants and a big black satin cape, and the other one was all in white, and he had red Bowie hair and an Aladdin Sane lightning bolt across his face. They looked so good, so I borrowed a pen from Tony Curtis and I wrote on a matchbook. I drew Saturns and lightning bolts and moons and stars, and I just wrote ‘Aladdin Sane, you cosmic organism, call me’ and I threw the matchbook in the direction of the seats. The next day they called me on my landline at my mom’s house.

That was George Ruthenberg and Paul Beahm, who turned out in a few years to be Pat Smear and Darby Crash [from LA punk band The Germs]. Pat was my first boyfriend in Los Angeles, and I was his first girlfriend ever. Years and years later after that, I went up to Seattle to interview Nirvana at Kurt Cobain’s request, because I had given Courtney Love her first gigwhen I was booking punk clubs, and I had also written a story about them. I went up there, and Kurt and me got along really well. But in an interview situation, he was being pretty quiet, and the rest of the band was being super quiet. [At the time] Pat had just joined [the band]. I’d ask a question and I’d get monosyllabic responses, and finally Pat looked at me, and he just kind of nodded. Then he said [to the rest of the band members], ‘You guys, Pleasant isn’t normal. When she was fifteen, she took away my virginity.’

Not that long after, I did one of the last interviews with Kurt when he came down to LA and I brought him to some drag show cabaret. He was super interested in it. Nobody knew who he was, but he was really cute, and all the queens were picking up on him. I had told him to get this book called Death Scenes, all about vintage teens and ’20s through ’50s crime scenes in Los Angeles, and we were reading it on the phone together. That turned into what I think is the last interview ever published [with him].

How and why did you get drawn into punk?

I knew who everybody was—people like Kim Fowley and Rodney Bingen-heimer and all the bands from LA—[from] reading rock’n’roll magazines. This is going to sound so mercenary, and I can’t believe I was fifteen when I did it, but I would just go up to people and say ‘Oh hey’ to their first name, and then they would just start talking to me, thinking that we knew each other. So then I just knew everybody, really quickly. I wound up working at the Whisky round about the time I turned sixteen because I was there everyday anyway, and [the manager] used to check all the kids’ school reportcards. If you had a C+ average, he’d let you in for free.

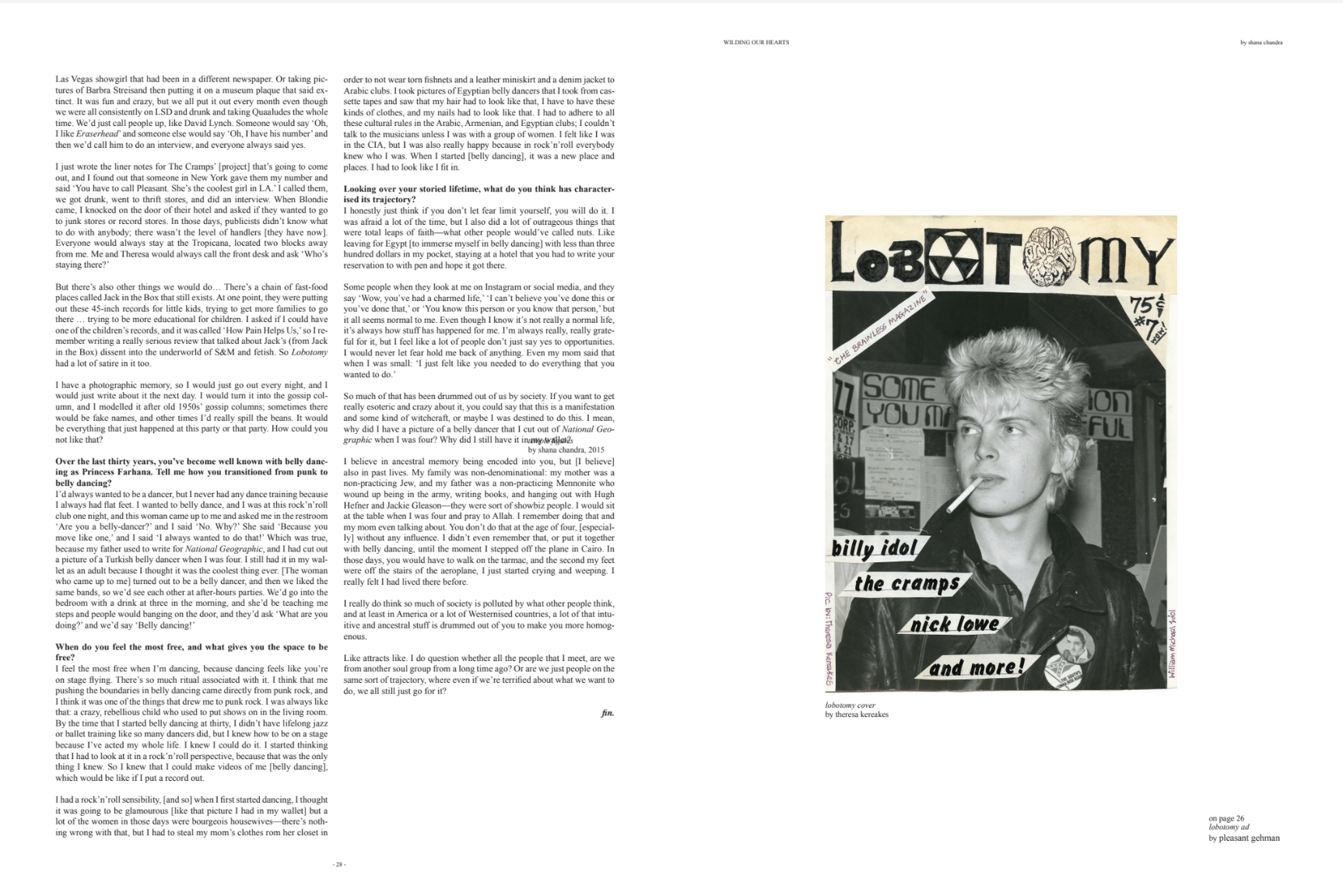

I was working as a ticket-taker, and then I had one of the first fanzines inLA, called Lobotomy, a xeroxed fanzine. I went to the booking lady [forWhisky a Go Go] and asked if we could do a fundraiser for the magazine,and she said yes. The gig had The X, The Alleycats, The Germs, and whenyou look at the marquee now you go ‘Oh my God!’ Even then it was a sellout, because then, there weren’t many places that allowed punk rock, but those people were just my friends. They were popular bands then but not what they evolved to be.

When I look back on my life, I really think it’sdestiny. Anything that I’ve wanted to do, it’ll drop in my lap, and I’ll just say yes to the opportunities. It unfolds like crazy.

Lobotomylaunched the careers of so many people who worked on it, including yours. What do you think made the zine so special that made it cult and that people began to take notice of it?

I know that I’ve always been able to write. My father was a writer, my mother was a singer and dancer and then a writer, and my uncle was a hugely respected jazz critic. Everyone in my family was in the arts. My writing was really good, and I’m not saying that from ego. I would read magazines and just wonder ‘Why didn’t they say this?’

All my friends used to write with me: Jeffrey Lee Pierce from the Gun Club, Kid Congo Powers wrote for it before he was in The Gun Club and The Cramps, Randy Kaye who was my co-editor—we used to cut school every day to work on it—and Theresa Kereakes [who] was a wonderful photographer. Everyone was super talented. There wasn’t gifted kids programs in those days, so we just made our own thing. We went out every night and watched all these bands when they were so young, like Blondie and The Cramps and The Damned—anybody you can think of. Me and Randy used to cut school to see The Runaways practise because Joan Jett was his best friend, and then she was my best friend. It was a conflux of kids that didn’t fit into normal society, but when we all found each other, it was incredible.

Lobotomy had an incredible bunch of people working for it, in an incredible scene that was probably hundred people or less who were all also incredible, doing things like starting record labels or bands or doing art. There was no limits then. I still don’t understand how we all found each other in punk rock. It was like in that movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, when everyone that’s making mounds in mashed potatoes find each other in front of the alien craft.

We would get drunk and put Lobotomy together; we would laugh so hard. I would make collages out of newspapers. I remember putting JohnnyRotten’s face that I cut out of NMEmagazine... on top of an ad for a Las Vegas showgirl that had been in a different newspaper. Or taking pictures of Barbra Streisand then putting it on a museum plaque that said ex-tinct. It was fun and crazy, but we all put it out every month even though we were all consistently on LSD and drunk and taking Quaaludes the wholetime. We’d just call people up, like David Lynch. Someone would say ‘Oh, I likeEraserhead’ and someone else would say ‘Oh, I have his number’ and then we’d call him to do an interview, and everyone always said yes.

I just wrote the liner notes for The Cramps’ [project] that’s going to come out, and I found out that someone in New York gave them my number and said ‘You have to call Pleasant. She’s the coolest girl in LA.’ I called them, we got drunk, went to thrift stores, and did an interview. When Blondie came, I knocked on the door of their hotel and asked if they wanted to go to junk stores or record stores. In those days, publicists didn’t know what to do with anybody; there wasn’t the level of handlers [they have now]. Everyone would always stay at the Tropicana, located two blocks away from me. Me and Theresa would always call the front desk and ask ‘Who’s staying there?’

But there’s also other things we would do... There’s a chain of fast-foodplaces called Jack in the Box that still exists. At one point, they were putting out these 45-inch records for little kids, trying to get more families to go there ... trying to be more educational for children. I asked if I could have one of the children’s records, and it was called ‘How Pain Helps Us,’ so I remember writing a really serious review that talked about Jack’s (from Jack in the Box) dissent into the underworld of S&M and fetish. So Lobotomy had a lot of satire in it too.

I have a photographic memory, so I would just go out every night, and I would just write about it the next day. I would turn it into the gossip column, and I modelled it after old 1950s’ gossip columns; sometimes there would be fake names, and other times I’d really spill the beans. It would be everything that just happened at this party or that party. How could younot like that?

Over the last thirty years, you’ve become well known with belly dancing as Princess Farhana. Tell me how you transitioned from punk tobelly dancing?

I’d always wanted to be a dancer, but I never had any dance training because I always had flat feet. I wanted to belly dance, and I was at this rock’n’roll club one night, and this woman came up to me and asked me in the restroom ‘Are you a belly-dancer?’ and I said ‘No. Why?’ She said ‘Because you move like one,’ and I said ‘I always wanted to do that!’ Which was true, because my father used to write for National Geographic, and I had cut out a picture of a Turkish belly dancer when I was four. I still had it in my wallet as an adult because I thought it was the coolest thing ever.

[The woman who came up to me] turned out to be a belly dancer, and then we liked the same bands, so we’d see each other at after-hours parties. We’d go into the bedroom with a drink at three in the morning, and she’d be teaching me steps and people would banging on the door, and they’d ask ‘What are you doing?’ and we’d say ‘Belly dancing!’

When do you feel the most free, and what gives you the space to be free?

I feel the most free when I’m dancing, because dancing feels like you’re on stage flying. There’s so much ritual associated with it. I think that me pushing the boundaries in belly dancing came directly from punk rock, and I think it was one of the things that drew me to punk rock. I was always like that: a crazy, rebellious child who used to put shows on in the living room. By the time that I started belly dancing at thirty, I didn’t have lifelong jazz or ballet training like so many dancers did, but I knew how to be on a stage because I’ve acted my whole life. I knew I could do it.

I started thinking that I had to look at it in a rock’n’roll perspective, because that was the only thing I knew. So I knew that I could make videos of me [belly dancing], which would be like if I put a record out. I had a rock’n’roll sensibility, [and so] when I first started dancing, I thought it was going to be glamourous [like that picture I had in my wallet] but alot of the women in those days were bourgeois housewives—there’s nothing wrong with that, but I had to steal my mom’s clothes from her closet in order to not wear torn fishnets and a leather miniskirt and a denim jacket to Arabic clubs.

I took pictures of Egyptian belly dancers that I took from cassette tapes and saw that my hair had to look like that, I have to have these kinds of clothes, and my nails had to look like that. I had to adhere to allthese cultural rules in the Arabic, Armenian, and Egyptian clubs; I couldn’t talk to the musicians unless I was with a group of women. I felt like I wasin the CIA, but I was also really happy because in rock’n’roll everybodyknew who I was. When I started [belly dancing], it was a new place and places. I had to look like I fit in.

Looking over your storied lifetime, what do you think has characterised its trajectory?

I honestly just think if you don’t let fear limit yourself, you will do it. I was afraid a lot of the time, but I also did a lot of outrageous things that were total leaps of faith—what other people would’ve called nuts. Like leaving for Egypt [to immerse myself in belly dancing] with less than three hundred dollars in my pocket, staying at a hotel that you had to write your reservation to with pen and hope it got there. Some people when they look at me on Instagram or social media, and they say ‘Wow, you’ve had a charmed life,’ ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this or you’ve done that,’ or ‘You know this person or you know that person,’ but it all seems normal to me. Even though I know it’s not really a normal life, it’s always how stuff has happened for me.

I’m always really, really grateful for it, but I feel like a lot of people don’t just say yes to opportunities. I would never let fear hold me back of anything. Even my mom said that when I was small: ‘I just felt like you needed to do everything that you wanted to do.’So much of that has been drummed out of us by society. If you want to get really esoteric and crazy about it, you could say that this is a manifestation and some kind of witchcraft, or maybe I was destined to do this. I mean,why did I have a picture of a belly dancer that I cut out ofNational Geo-graphic when I was four? Why did I still have it in my wallet?

I believe in ancestral memory being encoded into you, but [I believe]also in past lives. My family was non-denominational: my mother was anon-practicing Jew, and my father was a non-practicing Mennonite who wound up being in the army, writing books, and hanging out with Hugh Hefner and Jackie Gleason—they were sort of showbiz people. I would sit at the table when I was four and pray to Allah. I remember doing that and my mom even talking about. You don’t do that at the age of four, [especially] without any influence.

I didn’t even remember that, or put it together with belly dancing, until the moment I stepped off the plane in Cairo. In those days, you would have to walk on the tarmac, and the second my feet were off the stairs of the aeroplane, I just started crying and weeping. I really felt I had lived there before. I really do think so much of society is polluted by what other people think, and at least in America or a lot of Westernised countries, a lot of that intuitive and ancestral stuff is drummed out of you to make you more homog-enous. Like attracts like. I do question whether all the people that I meet, are we from another soul group from a long time ago? Or are we just people on the same sort of trajectory, where even if we’re terrified about what we want to do, we all still just go for it?